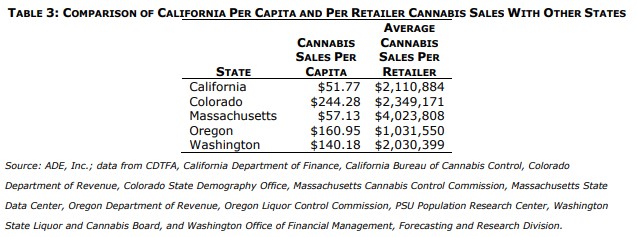

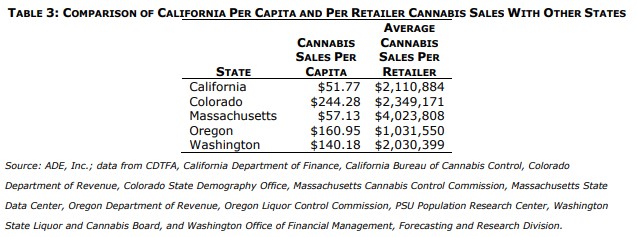

While it’s nice to think that every state that legalizes weed has suddenly been transformed into a magical marijuana paradise, the truth of the matter is a bit different. In reality, states that have legalized have left it to local authorities at the municipal level to determine whether legal weed is right for their area. Many areas of states we might assume to be “all in” on legalization have eschewed the legal stuff — and that’s caused an illicit market to thrive. A study confirms what the era of alcohol prohibition should have taught us long ago: local marijuana bans spur alternative means to procure pot. This has financial consequences, too.

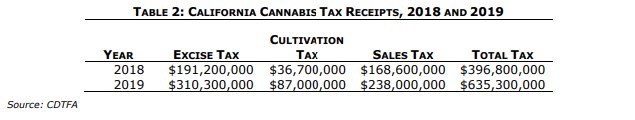

Although there remains controversy around some bills that have legalized commercial weed while prohibiting growing for personal use, there’s also the eternal debate of whether a plant should be regulated and taxed. Legalization efforts for years stalled, in part because advocates were resolute in simply flipping the “legal” switch, without many of the provisions we’ve seen passed in the last 20 years. Many states have happily implemented testing and taxing regimens for pot producers and sellers, and the dollar signs have helped push legalization in several states.

It can be expensive to start an operation, of course. Becoming and staying a legal weed producer or distributor means not only paying taxes, but in some cases a business owner must add in testing costs, licensing costs, and the overhead of a physical establishment that meets specific criteria. These expenses are passed on to consumers, which means there’s likely an illicit market everywhere. But it also means in places where weed is legal the alternatives are lower-quality products or even harmful ones, as we’ve seen with counterfeit cartridges.

The study shows that some areas of California have been dragging their feet when it comes to licensing legal weed shops. As just one example, Stockton, which just implemented its own tax and licensing structure last year (at 5%), could see nearly $4 million in tax revenues on the high end. On the low end, revenues could be over $800,000. At a time when cities are suffering due to a pandemic that is dragging the economy down with it, those sorts of tax revenues could really help.

And yet, another case study was San Bruno, which has no legal weed operators. The city has put a ballot measure for a 10% tax up for a November vote, but the city has yet to realize any revenue because of its delay. It could rake in over a million dollars on the high end, says the study. It’s possible that those tax revenues would go up over time, too, as more stores open up and more people become used to it.

Even so, it’s not like those cities are devoid of weed sales. The government just isn’t involved, and no taxes are being collected. While the debate rages on whether marijuana should be taxed at all, for now California cities would be wise to employ any revenue generators they can. It’s inevitable that they’ll jump on board at some point, but it’ll take enough people to demand it before that happens.