A new study suggests “casual” marijuana use may lead to subtle changes in the structure of young adults’ brains.

“Just casual use appears to create changes in the brain in areas you don’t want to change,” said Hans Breiter, a psychiatrist and mathematician at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and one of the authors.

The findings of the study, which was published in the Journal of Neuroscience in April, drew national media attention. Reports suggested smoking pot a few times a week would lead to cognitive impairment and other negative consequences.

In fact, the study found no such thing. What’s more, like most research into the long-term consequences of cannabis use, it employed a small sample size, inconsistent definitions, and media hype.

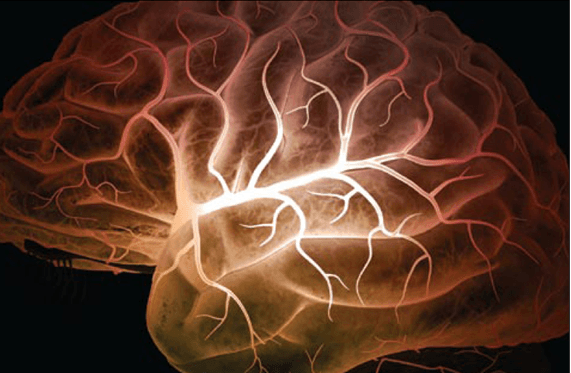

The study compared the brains of 20 “casual” marijuana users with those of 20 people who don’t use the drug. It looked at two critical areas of the brain, the nucleus accumbens and the amygdala, responsible for emotion and motivation.

Researchers saw differences in the volume, shape, and density of these regions, which may play a role in some mental illnesses. The more users smoked, the more change was seen.

Breiter’s study, however, is riddled with problems. The same problems plague many attempts at research into the long-term effects of weed.

First, the sample size of 20 users was ridiculously small. It’s very difficult to draw accurate conclusions from so few participants. Medical trials often require small test groups, but 20 is pushing the limit.

So is the study’s definition of a “casual” smoker. The average user in the study smoked a total of 11.2 joints on 3.83 days per week. That’s more than half the week, more than 5 grams, nearly three joints a day – hardly casual.

Other studies have labeled much lighter use “heavy.” In 2012, Janna Cousijn and her colleagues studied “heavy” smoking by users who consumed 3 grams each in an average week.

Breiter’s study also fails to draw a direct causal link between marijuana use and structural changes in the brain. At most, it demonstrates a correlation – the two are connected somehow, but one doesn’t necessarily cause the other.

It’s also possible, for example, that people who are wired to develop certain brain changes are also wired to seek out weed. And the pot smokers in the study drank more alcohol and smoked more tobacco than the participants in the control group, either of which could have played a role in the brain alterations.

Even more important, the researchers failed to prove that these structural changes cause any kind of cognitive deficit.

Finally, as usual, reports on the study imply its results apply to all cannabis consumers. That isn’t true. The study only deals with young adults.

Gregory Gerdman, a biologist and neuropharmacologist at Eckerd College in Florida, said it’s concerning that studies like this are funded by grants from agencies such as the Office of National Drug Control Policy, whose mandate is preventing drug use.

“If you’re getting money from the drug czar’s office, that money’s not going to continue if you don’t end up publishing something that at least supports the general story of the danger of drug abuse,” Gerdman said.